Deleting emails will not save the planet

A while ago I saw a post on LinkedIn that piqued my interest, not because it was any good, but because it was impressively wrong. It claimed that, to quote, “if every email user deleted just 10 emails, it would save enough electricity to power millions of households each year”. This is not only wrong, it is obviously wrong. In this post, I’d like to dive into why it’s wrong, how one might come to think it’s right, and perhaps what better message you could put out there to save the planet.

The claim is not even unique to LinkedIn, it has been widely circulated in the news, with variations on the severity of the claims, such as on national television complete with terrible data security advice, the BBC, as well as various other outlets. That kind of attention doesn’t appear out of nothing, so let’s examine the claim a bit further.

Why it’s wrong

Houses are big, and emails are not. This is an intuition that I think we can start from. For the savings of 80 billion deleted emails to power millions of houses, they have to be expensive to save. This is not, in fact, the case. Let’s do an oversimplified comparison.

At the time of writing, there are 2587 emails in my inbox, which weigh a total of 167MB1. This works out to an average of 61kB of data per email. More than I expected, but as we will see, not that much. Assuming all eight billion people alive2 today delete ten emails, that works out to roughly five petabytes ( bytes) of data.

A petabyte is a lot of data, but not that much by today’s standards. You can buy an 18TB hard drive for €280 so for the low, low price of €77 thousand you too can store this much data. Alternatively, you could pay for Google Cloud Storage, and store all that data for about €92 thousand a month, going as low as €5.5 thousand a month if you opt for Archive Storage. Since we’re talking about emails we would otherwise delete and therefore can’t be that valuable, I’d argue that archive storage will do nicely.

With our calculations above, we now have a good enough picture of what the potential savings are of us deleting all of those emails. We cannot directly compare the monetary cost of storing this data to the carbon footprint of the power consumption of millions of homes, but we can make a good guess that it doesn’t compare. Considering that the average household over a thousand euros a year on energy (both power and heating) a year, multiplied by millions of households, it should be obvious that there are several orders of magnitude in between them in terms of cost.

How do these claims happen

“Why do people believe things that are false” is a big question that I am not qualified to answer. For the claim central to this article, however, we can make some educated guesses. Searching for the origin of this claim, led me to this article about the footprint of an email. In the article, it is claimed that the carbon footprint of a longer email sent from a laptop and read on a laptop causes the equivalent of 17 grams of CO2 to be emitted. There are a few caveats to this number but let’s assume that it’s true. This gives us a CO2 “compensation” of 138 thousand tonnes.

Now for our millions of households. I’m going to take the numbers for the Netherlands because I live there, but other European countries should be similar. According to the Central Bureau for Statistics, the average household uses 2640 kWh of electricity annually. Our World in Data mentions that on average, the Netherlands emits 325 grams of CO2 per kWh of energy. Putting that all together and solving for the number of households gives us:

Not quite millions of households, but at least a single million. This number is directly proportional to the carbon footprint of an email, and that’s gone down over the years. This is unfortunately where things stop lining up. The carbon footprint of an email, as written by Berners-Lee, is not in its transport, nor the electricity. It’s in the embodied carbon of your laptop. While the book doesn’t provide figures for a laptop, other than noting that it has more embodied carbon than a phone, for a phone this looks something as follows:

Overview of the carbon footprint of sending and reading an email via the smartphone. Figure reproduced from “How Bad Are Bananas” page 17. Very little of the CO2 impact of the process is related to its electricity use.

“Embodied in the phone” in this case means that the CO2 was emitted in the process of creating the phone, averaged out over its lifetime, for the duration of dealing with the email. In a fun twist of events, it causes more CO2 to delete the emails, as you will be spending time and energy on doing those actions. There are of course caveats to that too, and eventually, the amount of data does start to matter.

One thing that is interesting to note, is how little CO2 is involved with producing electricity these days. My recent bike trip in June back and forth to Den Haag, about 27 kilometers, had a carbon footprint comparable to 2 days of my domestic electricity use.3

Why make a point out of this

You might be asking yourself, why anyone would go through the trouble of fact-checking a claim that as posted on a social media platform largely without consequences or persistence. And the answer to that is twofold. The first part is very simple.

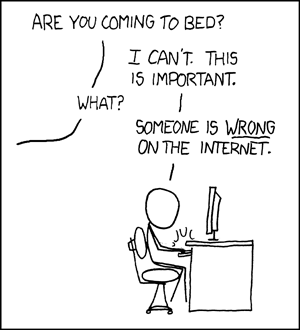

We can’t just let people onto the internet and have them tell lies. XKCD 386.

The second part however is more personal, so bear with me as I step on my soap box. The climate change discussion has long been poisoned by less than truthful information. Big institutions pay a lot to pretend there’s any debate at all that the climate is changing. Sweeping changes will have to be made by every single country around the world. For some, it may already be too late.

Claims like the one that sparked this article do not deny the need for change, but they are in my opinion harmful in different ways. In a small part, they give climate deniers ammunition (“Look at these ridiculous claims, who knows what else they might be lying about”) but as part of the bigger picture they maintain the illusion that climate change is a personal issue that will be addressed if we all do our part. That is not the world we live in.

Berners-Lee, in his book, champions the 5-tonne lifestyle, where everything you do in life should amount to no more than 5,000 kilograms of CO2 equivalent emissions per year. This is a noble goal and one that I respect immensely. The world would be a better place if more people lived like that. This is, for reference, about 40% of the average per capita emissions of the United Kingdom4. Unfortunately, it is not a structurally feasible solution in my opinion.

There is a lot of talk in politics about a carbon tax as if it’s something new, but we’re already there. Countries around the world are effectively already paying for it. My famously under-sea-level home country of the Netherlands has to invest in raising, widening, and doubling the dikes to deal with the rising sea levels. I live in a rich country and it will be fine for the foreseeable future. Many Pacific island nations will have to do similarly expensive work without those resources. A small number of countries benefited greatly from emitting greenhouse gases, boosting economies, and bringing wealth, but the costs of the warming planet are borne by the world as a whole as a worldwide flat tax. This won’t go away by itself either, due to the tragedy of the commons: everyone individually benefits by making more CO2 emissions, which inevitably makes life worse for everyone else.

The classic solution to this tragedy is to achieve consensus on how to manage the shared resources, which translates to worldwide treaties about emissions. The 2015 Paris Agreement was a step in this direction, though it does not appear to be doing nearly enough. We should as a planet agree where our priorities lie, and ensure that the environmental costs of our activities are properly priced in for those undertaking them, rather than borne by the world as a whole. Flying is the easiest example, due to plane fuel being barely taxed at all, but there are other examples.

While the tech sector is not nearly as big as that, carbon footprint wise, bitcoin still famously uses more energy than several developed countries, of which Finland is the most recent example I could find, though this number has likely changed significantly over the last three years. The “new” kid on the block, AI, is also growing significantly, and is expected to consume more energy than the entirety of the Netherlands. Going back to the classics, a lasting rumour stated that a single Google Search is roughly proportional to boiling a kettle of water, though recent estimates put that number far lower5. No matter what it is, its utility should be weighed against its cost.

The internet as a whole consumes a lot of power but it also brings a lot of utility. AI and recently large language models have been very powerful and can improve human productivity. Bitcoin is certainly a thing that exists. I do not mean to argue that we should abandon all that, though we should further incentivize computational efficiency, and reduce the carbon footprint of the power requirements that remain. Not just for tech, but for everything, and not just as an ideal, but as global policy.

Take away

To get back to the original topic and maybe contradict this article’s title a little: individual actions can’t solve the problem, but they can help. You could eat less meat or dairy. You could avoid flying. The concept of a carbon footprint isn’t without merit. It is a good teaching tool to make people aware of the impacts of their actions.

Even though the cost of an email is small, that doesn’t mean that you can send as many of them as you want. People send more emails today than they would’ve ever sent traditional mail, and so the carbon saved from winding down the post service is more than compensated for by the additional emissions from email.

You won’t save the planet by deleting emails, but sending fewer emails is still a good goal to have, just as any small improvement can be, as long as we don’t forget the big picture. Try to unsubscribe from all of those marketing emails. Design your web apps to not triple confirm every single thing that happens. And if you’re discussing details that need some figuring out, maybe don’t send a follow-up email every day. Phil, if you’re reading this, stop it. You’re stressing me out.

During the writing of this article I reached out to mr. Berners-Lee for comment, whose assistant thanked me for getting in touch, but declined to comment due to time constraints.

-

This is the on-disk size, so every email is rounded up to the nearest full page (4096B) of data. ↩︎

-

At the time of writing, there were 8,122,973,678 people alive according to Worldmeters.com. Parents will have to compensate for their infants, who might not have ten emails to delete yet. ↩︎

-

Generously assuming 120g/km based on “Cycling a mile”, How Bad Are Bananas p. 33, and my flexitarian diet. ↩︎

-

“How can I cut my footprint?”, p. 196, How Bad Are Bananas. ↩︎

-

0.5g to 8.2g depending on specifics, “A Google Search”, p. 18, How Bad Are Bananas ↩︎